Estimated read time: 9-10 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY – The Utah law known as GRAMA — the Government Records Access and Management Act — went into effect in the summer of 1992, allowing the public access to government records.

That same year, commercial dial-up internet made its debut and the first text message was sent, changing communication forever.

Three decades later, we communicate through emails, text messages and an ever-growing plethora of digital apps. The most powerful among us do, too.

So how has that changing communication impacted access to public records?

"It doesn't matter what the physical form of the record is," explained Utah attorney Jeff Hunt, who helped draft GRAMA. "Whether it's an email, a text message, something on Twitter, or Facebook, all those are records under GRAMA."

Hunt says frequent changes to GRAMA with each legislative session ensure the law continues to evolve, but some believe modern-day communication has outpaced GRAMA's ability to deliver on the promise of government transparency, particularly when it comes to lawmakers' communication records.

Testing transparency

Jonathan Bejarano has filed too many GRAMA requests to count.

"I'm trying to quit though," the researcher and Utah resident joked.

For the most part, Bejarano said using GRAMA has allowed him to obtain records that give him a better understanding of what government officials are doing and why.

But that wasn't the case when he tried to use GRAMA to get a particular text message that he knew existed, at least at one point in time.

"I came across a video of Senate President Stuart Adams talking about how he received a text message, talking about Donovan Mitchell," he said. "And I was really curious. I wanted to know context."

The video Bejarano saw was obtained by the Center for Media and Democracy through a records request and showed Utah Senate President Stuart Adams, R-Layton, discussing a text message he received about the Utah Jazz player and the Legislature's stance on critical race theory.

"I just got a text last night and I hate to use names, but I will," Adams is seen saying in the video. "Donovan Mitchell is not happy with us."

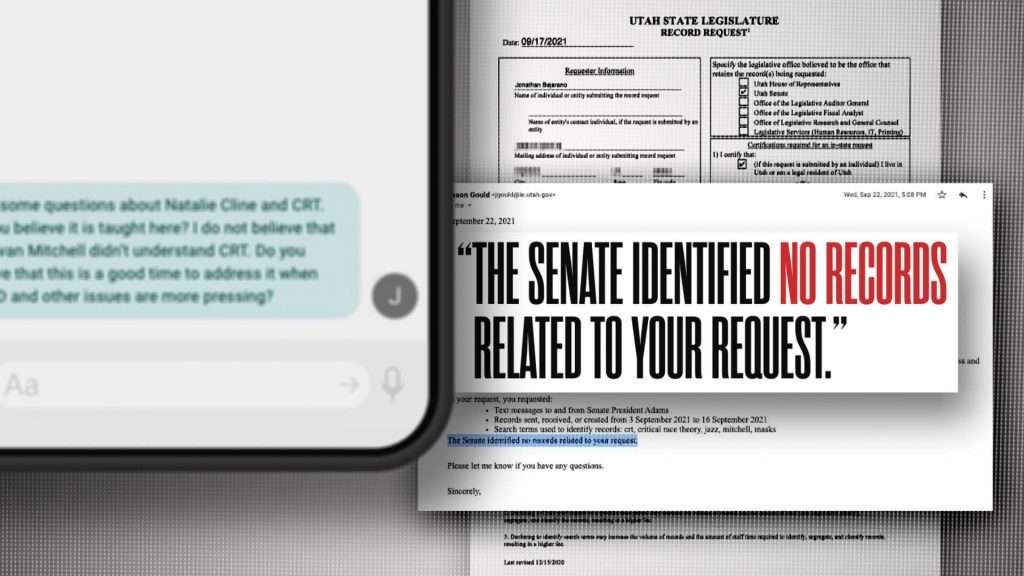

Bejarano filed a GRAMA request seeking texts from Adams' phone including keywords like "CRT" and "critical race theory" but received a response from the Senate the next day saying no responsive records were identified.

That's when he decided to conduct his own transparency test.

"I was like, 'OK, let me try something.' And so, I texted Senate President Adams, and it's like, 'Hey, what about critical race theory?'" Bejarano explained.

He then sent another GRAMA request seeking text messages from Adams' phone and included keywords found throughout his own text, expecting to at least receive a copy of the record he'd created.

But he received the same response: "The Senate identified no records related to your request."

"It makes me a little upset," Bejarano said, "because these people are elected to represent us."

Bejarano said he reached out twice to ask about an appeal process, but the Legislature stopped responding after his second follow-up email.

The KSL Investigators reached out to Adams and Senate staff about the records request and requested an interview.

In an emailed statement, Deputy Chief of Staff Aundrea Peterson said the Senate responded appropriately to Bejarano's request.

"Just because a record no longer exists or may have never existed, does not mean the statute or policy was not followed," she wrote.

Friday, the day after this report first aired, Senate staff contacted Bejarano. Together, they figured out why Bejarano's text message to Adams didn't exist. Bejarano had used the number Adams lists on the Legislature's website, which is a landline.

Bejarano would like to see the Legislature's records policy revisited. He believes lawmakers have found ways to skirt transparency, and some lawmakers told the KSL Investigators he's not wrong.

Private email accounts

"There's enough ways around GRAMA, and people don't like to hear that, but there are," said Rep. Andrew Stoddard, D-Sandy.

Stoddard sponsored a bill during the last legislative session seeking to clarify GRAMA.

"People were using personal devices for government business and not providing access to those records," he said. "So that's what it tried to do is just say, 'Hey, if you're doing this on a personal device, it can still be requested via GRAMA.'"

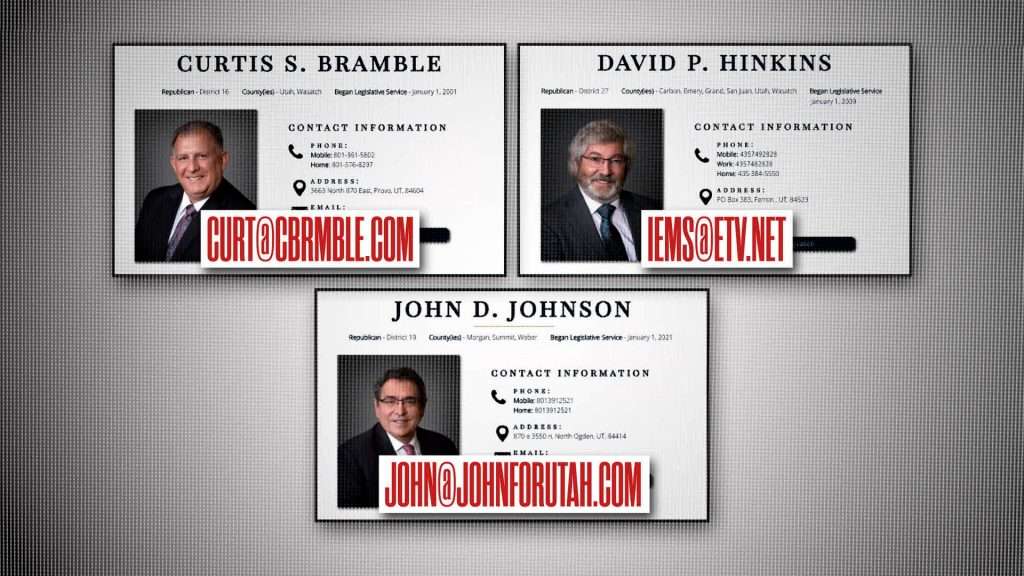

It's no secret that some lawmakers prefer to use private email accounts to do the public's business. The KSL Investigators have obtained email records showing multiple lawmakers using private accounts for legislative work. And Sens. Curtis Bramble, R-Provo; David Hinkins, R-Ferron; and John Johnson, R-North Ogden, openly list private emails in their contact information on the Legislature's website.

"That, to me, is a big red flag," said Bejarano.

In April, the KSL Investigators sent a survey to all 104 Utah legislators, asking if they use private accounts to communicate with other elected officials, state employees and constituents. Only 13 responded. Two are Republicans and 11 are Democrats.

Bramble said he uses a private account to ensure no one can accuse him of using his government email for campaigning.

Others said they try to keep personal and government communications separated in their respective email accounts, but it's difficult, as some constituents already have their campaign or personal email addresses and will use those to reach out.

"Constituents frequently contact me through other emails," said Sen. Kathleen Riebe, D-Cottonwood Heights. "I will forward emails to my state email if they come from state employees or elected officials. That does not happen that often."

While a couple of legislators who responded insist they always use their legislative email account for government business, others said they typically respond to people using the account initially used to reach out.

"Have I used private accounts? Yes," said Sen. Todd Weiler, R-Woods Cross. "But it hasn't been a, 'Haha, they'll never catch me.' It's just more of, someone's emailed me at that account, and I've responded to them."

Weiler, and others, said they are aware that if their communication records are requested under GRAMA, they are required to turn them over to the legislative records officer responding to the GRAMA request, even if the records exist in a personal account or on a personal device.

"Quite frankly, with my emails, I don't feel like I have anything to hide," said Weiler.

An honor system

When a request is made for emails in a legislator's government account, lawmakers told KSL they are instructed to not delete anything while a non-partisan staff member searches for responsive records. When a legislator uses a personal account, they are solely responsible for turning over responsive records.

"That would be on the honor system," said Stoddard.

Like Stoddard, Riebe believes Utah's GRAMA law is not adequately keeping pace with today's communication landscape.

"Social media and all other ways to communicate make this very difficult," she wrote in her response to the KSL survey. "Group texts that involve many electeds could possibly fall under the open meetings act. The nefarious, unintentional, and benign acts are lines that are blurry. Communication in any way, shape or form that creates policy or deals with the 'people's business' should be fully transparent."

Rep. Jen Dailey-Provost, D-Salt Lake City, echoed similar concerns, writing, "I think that oversight intended by GRAMA is good in theory but inadequate in practice. Technology allows for a lot of opportunity to subvert accountability, though I don't have clear ideas on how to fix the problem."

Hunt said GRAMA is already clear – anytime a lawmaker is doing the public's work, GRAMA applies.

"The rub is, how do you conduct searches for responsive records when someone makes a GRAMA request and you're searching for responsive records on a device that is privately owned that may contain some highly, you know, private material on it?" said Hunt.

As it stands now, Hunt said the device or account owner is typically the person in charge of searching for and identifying records responsive to GRAMA requests.

"At some point, we're all relying on the government to act lawfully to comply with GRAMA," he said.

Deleting records

Even when emails go through a lawmaker's government account, access to those communication records is not guaranteed.

In November, the KSL Investigators obtained several emails from outside sources. The emails discuss a new self-defense law and were sent to and from a legislative email account, but when KSL filed a GRAMA request seeking emails related to that bill, the emails we'd already obtained were never provided by the Legislature.

When KSL appealed citing the emails that were not turned over, the Legislature said there is no rule to prevent lawmakers from deleting emails if there is no "administrative need" for them.

"If I've got an email that I don't want anyone to see, I can go and delete it," said Stoddard. "And then obviously, it's not subject to GRAMA because it's not there."

The Legislature's retention schedule classifies communication records as "temporary," and states lawmakers can "review and discard when no longer needed."

"Once they're deleted, they're gone," said Weiler. "I typically have not played that game, but I know some legislators have because they've been advised to by people that are trying to help them."

Weiler said the retention schedule is likely open for discussion.

"I wouldn't necessarily be opposed to it," he said. "That would be an interesting debate. I think it goes both ways. A lot of people will email me with their problems, and they don't understand that KSL might be reading that email the next week or the next month."

'A giant red flag'

Bejarano believes lawmakers should be communicating through a government server that preserves those communications records, even when legislators clear their inboxes. He's also concerned about the Legislature's different appeal process for denials.

Unlike other public agencies and government offices across Utah, the Legislature is not subject to review by the State Records Committee, an independent body with the power to order the release of records that have been wrongly withheld.

"It was part of the bargain that was made when the Legislature made itself subject to GRAMA," Hunt explained. "The Legislature wanted to have the authority to set its own fees and it also wanted the authority to create its own appeal process."

Instead, the last option available to Utahns wishing to appeal a records denial from the Legislature is to request the Legislative Records Committee hold a hearing to reconsider the request, giving the Legislature the ultimate say in what records are released.

"They created the rules and they exempted themselves from them," said Bejarano. "I think that's a giant red flag."

"The Legislature is not transparent because they are essentially their own referee," said Bejarano. "They call the balls; they call the strikes."

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to reflect new information provided to Bejarano and KSL by the Senate after this report was published.